Jon told the Professor and Tam about seeing the pickpocket on the train but did not mention seeing the great black wing. He didn’t want the Professor to think he was telling stories, and Jon was unsure himself of just what he thought he had seen.

Tam was excited at the news about the thief. “If I see the little sneak about, I’ll make him give up that watch right enough,” he declared.

“Was your pocket watch terribly valuable?” Jon asked the Professor.

“I confess I don’t really know,” the Professor replied. “I myself treasured it. It was a gift from a good friend. But it was a thing only, not the friendship itself, and all things are transitory.” The Professor touched something near his collar, and Jon noted than he wore something strung about his neck, under his shirt.

“I won’t be able to sleep a wink,” Tam grumbled. “Thieving foreigners all over the place. We should keep alert, and take turns at sleeping.”

“I think we can be reasonably safe by taking the precaution of locking our compartment in the night hours,” the Professor said.

Tam still insisted on staying vigilant, but the rest of the long journey passed uneventfully, without signs of thieves or any more mysteries.

The train pulled at last into their station under a blazing midday sun. The land about was hot and dry, with a few gnarled and wind blasted trees and strange tumbled rock formations in the distance. The station stood at the center of a small sun-baked town of clay-daubed buildings and canvas awnings. Among the buildings, people went about all in foreign clothes, mostly robes and bright headscarves. Women carried very large and heavy looking baskets on their heads, while small children ran to and fro in dirty tunics or in nothing at all. Leaning out the compartment window, Jon smelled bad smells and good smells and all sorts of very new but very old smelling aromas in the hot air. Being home in Shandor smelled like clover and horses and little streams and cool winds tumbling down from the mountains to tell one about the cedars and pines they passed. Alarna smelled like spices and strange foods and sweaty people in very hot sun and perfume and old crumbly mud walls. It wasn’t crowded like Merigvon, where the crowd never ceased, but as the train pulled in it suddenly became crowded like an anthill. Carts pulled up and workmen bustled to unload one of the freight cars even as the train came to a full stop. Children crowded up around the train, calling out in languages Jon did not know, or perhaps in accents too thick for him to understand.

“Stay close to me as we disembark,” the Professor said. “There should be someone waiting for us.”

The hot wind hit Jon as he, Tam and the Professor stepped off the train onto a dusty platform, and Jon had to squint his eyes against it. He gripped the Professor’s hand, so as not to lose him.

“Eabrey!” the clear and pleasant voice of a woman exclaimed. “We’re over here.”

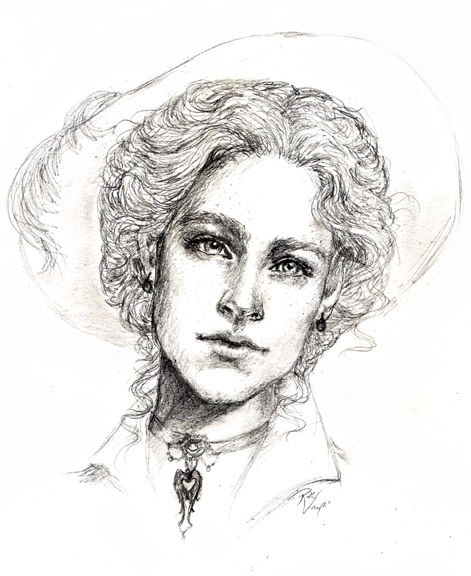

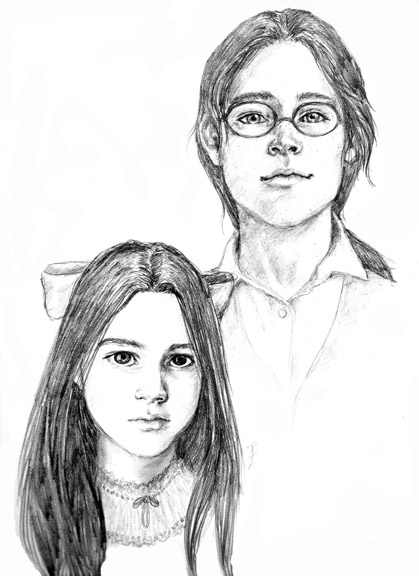

Jon turned, still squinting a little, to see a small greeting party waving at them from under a large green sun parasol. The woman who had addressed the Professor by his first name was very pretty and wore clothing finer and more fashionable than anything Jon’s mother owned. She looked like something from the papers, with a pile of dark copper-colored hair pinned up on her head and a brimmed hat with feathers. Her face was merry and freckled and she waved an ungloved hand at them. Beside her were two children, a boy with spectacles who looked only a little taller and older than Jon, and a small girl with a solemn face and ribbons in her long black hair.

The Professor brightened. “Hellin, how good of you to meet us.” He led the boys down off the platform to stand before the lady. “Lady Blackfeather, may I introduce you to Tam and Jon Gardner, of Markerry, Shandor.”

Tam nodded his head to the lady, a little awed, and Jon did the same, “Lady,” he said, not sure how best to address her.

She smiled at them both. “Call me Hellin. It’s lovely to meet you at last. How was your journey? Set those bags down at once. Porter! Do please put these in the carriage, thank you. This way. Would you gentleman care to stop for some refreshment before we head for the dig? We shall.” Lady Blackfeather herded them all about as quickly as she had the porters, not giving them time to respond past nods and murmurs. The spectacled boy gave Jon and Tam a friendly grin. They all found themselves bundled past reaching children and loud merchants who shoved their wares forward in handfuls, into a shop across the street. Jon tumbled down into a chair beside Tam’s. He found himself exchanging an awkward stare with the girl with hair ribbons across from him, before a waiter set a tall pitcher of mint water and a platter of sandwiches between them.

Across the room, the Professor guided Lady Blackfeather aside and they spoke too quietly to be heard by the children. The boy with spectacles took the opportunity to address Jon. “You’re Jon, right? I’m Djaren Blackfeather.” Djaren had straight dark hair tied back in a tail like the Professor’s and green eyes, bright and eager behind his spectacles. He grinned at Jon. “I read your essay. I thought it rather brilliant. I’m so glad you’ve come.”

Jon blinked, startled. “I, I’m glad you liked it. I didn’t know Doctor Blackfeather had children.”

“Well, he does, and we’re them.” Djaren grinned again.

A small pale hand pushed the plate of sandwiches a few inches to the left, and the serious girl with hair ribbons peered at Jon again.

“This is my sister Ellea.” Djaren gestured to the little girl, who was regarding them now unblinking, with the same sober face she had kept since they first saw her. Jon found her gaze a little unsettling.

“Hello,” he said. “I am pleased to make your acquaintance.”

“Likewise,” Ellea said, taking a sandwich.

“Hear hear,” Tam said amiably, taking four of the small sandwiches, which all fit in one of his hands. “These are funny little things. Would you like some of the water with the leaf bits?” he asked Ellea. She nodded and he helped lift and pour from the large pitcher.

Djaren pushed the sandwiches toward Jon. “Mother says your essay was best because you have a real observational eye and take the time to think things out, rather than ramming hypotheses about like runaway carts. You’re mad bright too.”

“Um, thanks.” Jon accepted a cup of mint water from Tam, and fished out a mint leaf with his spoon, suddenly shy.

“Djaren dear, thank you for continuing our introductions.” Lady Blackfeather floated over in folds and ruffles of nice fabric and snagged two glasses of water and a little plate of sandwiches. “Do entertain our new guests. I am sorry, gentlemen, if I neglect you. I must have another moment with Professor Sheridan.”

Tam and Jon nodded, and Lady Blackfeather excused herself and the Professor to a separate table across the shop, where she made him drink a full glass of water before they began to speak again in low voices. Jon wished he knew what they were talking about.

Tam seemed to have the same impulse. “Ten to one it’s about the theft,” he said.

“Theft?” asked Djaren, with interest.

Jon and Tam spoke over one another telling all about the theft in the station and the pickpocket on the train. Djaren and Ellea listened with great interest. “But what was in Uncle Eabrey’s satchel?” Ellea spoke again in her careful quiet voice. “Thieves don’t steal papers. They don’t sparkle.”

“That’s a good point,” Djaren agreed with his mouth full. “What were they after? It isn’t as if Uncle Eabrey looks the least bit wealthy.”

“He’s your uncle?” Jon asked, surprised.

“More or less. Good as,” Djaren explained. “Father and he grew up together like brothers, from the time they were boys. Father always sort of looks out for Uncle Eabrey, and Eabrey’s always looking for clues to help with Father’s cause. They’ve worked together for ages.”

Ellea smiled oddly over the shrinking pile of sandwiches, and delicately sipped her mint water.

“He didn’t seem much upset by the theft,” Tam said. “He said nothing valuable was lost.”

“And that’s odd too,” Djaren said, “because the only thing he ever gets really worked up about is his research, and what he’s uncovered.”

Jon was still keeping an eye on the grown-ups, and so he noticed when the Professor pulled the ebony feather from his breast pocket, and handed it across the table to Djaren’s mother, who took it with a secret smile, and tucked it carefully into her hat.

“Well, everything seems in order,” Hellin said, returning to them with the Professor at her side. “Your packages should be ready to collect and then we can be on our way. Djaren dear, do collect up the copper pieces will you? Leave a half silver.”

Of course,” Djaren said amiably, resorting small coins on the tabletop. “We collect coppers,” he explained to the Gardners. “You never know when you’ll need a penny.”

“Aren’t silver more handy?” Tam asked.

“Only if you plan to spend them like money,” Ellea said.

Djaren handed the last two sandwiches to Tam and Jon to pocket. “At last! Come on!” He gestured them along with him out the door and into the hot street again. “I order the papers, three of them, but they only come in once a month. Along with any books we order in. We didn’t come into town last month so now I’m two months behind, and I’ve had nothing new to read. It’s intolerable.”

“We’ve got papers,” Tam offered, keeping step beside the shorter Djaren. “The Professor got a lot of them.”

“Really? Good! Then Anna and I can have at them at once. She’s following some story or other in the Times, and I was worried we’d have a fight for the first paper.”

“That story?” Tam looked a little befuddled. “Well, it doesn’t end. Not as yet anyhow. The lady just faints a few more times.”

“I think,” Ellea said, “that she is being poisoned.”

“And I told you,” Djaren sighed, regarding his sister, “that Arienish women are always fainting.”

“No one faints that much. She’s dying, and just doesn’t know it yet. All her silly troubles will be for nothing because she is going to her grave in a year. It’s inevitable.”

“Well, don’t you go telling Anna that,” Djaren said. He looked at the Gardner boys. “My sister is very cheerful, as you’ll notice.”

Ellea stuck out her tongue at her brother, somehow primly.

Jon exchanged a look with Tam and grinned. He was beginning to quite like the Blackfeather children. He exchanged a glance with Tam, a little smile to see if he felt the same way. Tam smiled back and nodded. “It’s a terrible heat, but the folk are good,” he told Jon. “Mind you wear your hat.”

* * * * *

Kara watched, hot, hungry and annoyed, from under a wagon as the strange little entourage passed. The bug-eyed boy was walking beside a little princess in hair ribbons with a frock that looked like ruffles and frosting. The lout was there too, and the skinny man with all the scars, whose watch was now in her pocket. A very fancy lady was talking with him and showing them all to a dusty carriage. Mostly Kara glared at the new boy. He was particularly annoying. He could pass as easily for a girl as Kara did for a boy. Kara at once disliked the arrogant turn of his head, his long hair, fine features, and pretentious spectacles. He obviously had far too high a regard for himself. You could tell by how he smiled all the time and never seemed to shut up.

Kara was so busy watching them that she nearly missed her chance to roll unnoticed from under the wagon before it began to lurch away. She blamed this on the heat and her now raging hunger. She swore and followed silently behind some workmen carrying trunks, hefting a heavy canvas bag of things she had collected in the baggage car. She entered the crowd at the next corner, safely anonymous, and began searching for the sign for the next meeting place. Her sharp ears caught three dialects here, but trade common seemed most prominent, which was lucky. She didn’t understand the other two. She discouraged a smaller and far more amateur would-be pickpocket with a hard kick that made him curse and run off. She was just sizing up some of the local merchants as possible fences or marks, when she found what she was supposed to be looking for. Under a faded wooden sign depicting a red pitcher she found an old man leaning by the door in the shade. She planted herself in front of him with her hands on her hips and waited for him to take notice. After a frustrating moment he finally did.

“Ah, little one. I have no coins for you. Be gone!”

“That’s not what you’re supposed to say.” Kara gave the white-haired man a dark look. “Alehd mentioned you were a fool and half blind, but I don’t find that enough of an excuse.”

“What a temper the small one has,” the old man muttered to himself. He squinted down at Kara, and spoke in a hushed tone. “I have seen the least and the greatest of thieves, in all kinds and all manners, but you are the smallest they have ever sent me. Don’t you have some home to go to? This is no life for a little one like you. You will make your mother cry.”

Kara sighed and bit back curses. She would not stab him. The daft old fool looked honestly concerned about her. Getting old, getting soft, Kara thought. “My last home was a packing crate,” she growled. “I am tired, and I am hungry, and my mother is as dead as you are about to be if you go tell Negal that you have turned away the best lock pick in all Charesh and the five provinces of Corestemar.”

The man lifted both hands, palm up. “Easy now. I do not send you away. You are welcome here, little–” he caught Kara’s dangerous look, “–master lock pick.” He smiled as he said it, exposing gaps of missing teeth and a hundred new wrinkles. “But where is Alehd, is he not with you?”

“He missed the train,” Kara said shortly. “And he didn’t pay me for my work.”

“But there is work here in plenty.” The old man gestured to the doorway. “Here the finest of tomb thieves have gathered in my father’s time, and my father’s fathers. The tombs of Alarna have been my family’s living. Things have changed now with the new visitors. We have now not to steal from the dead, but from other thieves.”

Kara nodded slowly. “Archeologists.”

“And what are they but thieves themselves? It is all the same under the sky.”

“Don’t flatter them,” Kara said.

© 2007 Ruth Lampi

Coolest one yet!

Very good.