Tam quickly became bored and fidgety atop the carriage seat. He climbed down and tried stroking the horses’ noses, though whether to calm them or himself he wasn’t sure. Somewhere in the distance, one of those big clocks they kept up atop towers chimed. Not a nice, even set of strokes so that you could tell what hour it was, but a few notes of some song Tam didn’t recognize. Well, he didn’t need a clock to tell him it was getting dark. The sun had long ago gone down behind the tall, unnatural buildings, and soon the stars would be coming out. If you could even see stars here, with all the glowing streetlamps. A little boy about as tall as Djaren had come by earlier, with a long stick like some odd blacksmith’s tool, and lit the lamps.

Anna shouldn’t have gone into the house, Tam thought. The foreigners here weren’t right, and not just in the way all foreigners weren’t right. Everyone going in had looked sad, except for the ones who looked excited, and those two things shouldn’t go together. But Anna wasn’t hurt, wasn’t in any horrible danger. That stuffy fellow must be looking after her well enough.

Tam sighed, cleaned his boots on a scraper, told the horses to behave, and went to stretch his legs. He hadn’t gone far when a noise in the alley between two of the houses caught his attention. He went to investigate. The alley was dark, but enough light leaked from the tall, closed windows of the houses on either side to let Tam pick his way around rain barrels and cellar doors. The sound came again, from inside the house to his right. Tam looked back toward the street. No one was watching, so he climbed a barrel under one window and peered over the sill.

Between thick, patterned curtains he saw a dimly-lit, clean spare room, and over in one corner lay Kara, crumpled up in a heap. It looked as though she’d been crying. She clearly didn’t belong in this house. Tam wondered what had gone north with whatever nonsense she’d been up to. It wasn’t his business, of course, but it bothered him to see girls cry. Even testy, rude ones like Kara. He had some spare time, and she was clearly in trouble, so he figured he might as well lend a hand.

Tam clambered back down and examined the alley, looking for a way in. Further back along the house he found the servants’ entrance. Some delivery was taking place. Workmen unloaded a cart full of crates marked with foreign letters. Tam stood in the line for taking boxes and sure enough, the men in the cart handed him a box when he came up. He followed the man in front of him and walked right into the house. In a sort of rear parlor, the men were setting the boxes down in stacks at the base of some stairs. Instead of following them back out, Tam turned down a narrow hallway in the direction he’d seen Kara.

A small mournful sound brought him to the correct room. He pulled the door shut behind him, in case someone might happen by, but didn’t latch it. “Kara! What are you doing all a mess in a strange house? What’s done you in, then?”

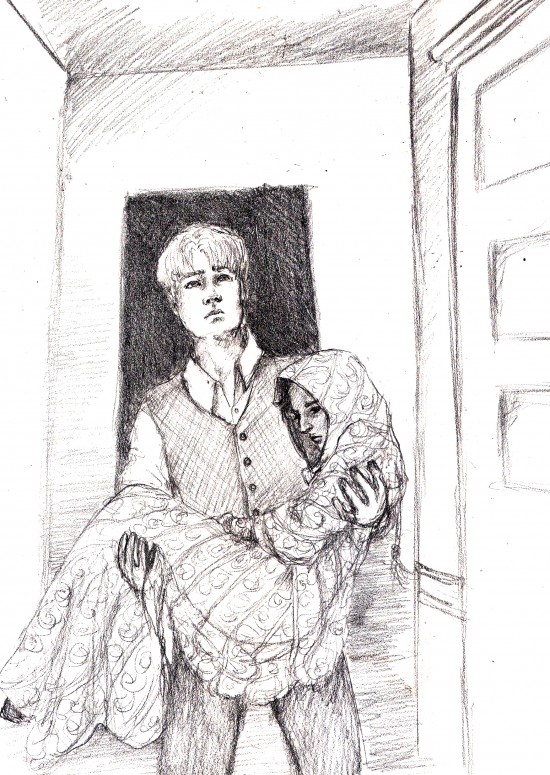

The small dark-skinned girl lay all twisted and curled in a ball, with what looked like a curtain tie loosely tangled about her feet. She wasn’t obviously hurt, but she wasn’t well either. She opened her mouth, eyes wide, angry and frightened. Barely a sound came out. Tam bent and scooped her up in his arms. It was easy. She was light and, to his surprise, did not kick. She opened her mouth again. Her voice came, very small. “Help.”

“Right. Course I will.” Tam smiled in what he hoped was a reassuring way, and turned to go out.

The door wasn’t where he’d left it. It stood, contrarily shut and latched, on a different wall altogether. Tam frowned. “That’s not right.”

Kara hissed, and managed two words. “Bad place.”

Tam carried Kara to the window, since it had not moved and he didn’t trust the new door. The evening outside was clear, but a torrent of rain ran down the inside of the window, pooling on the sill and dripping onto the floor. As Tam stood, puzzling over this, his breath on the windowpane suddenly frosted over, obscuring the view. With an odd cracking sound all the water turned to ice. Tam jumped backward. Well, it had looked like a steep drop down to the ground in the first place. They would just have to use the door. Tam turned, frowning, to find the old door back, and no less than two new ones.

“I don’t care for these goings on,” he said.

“Don’t say,” Kara muttered, sarcastic even with limited words. She was shivering. Edging warily near to the icy window, Tam pulled down one of the curtains, a bright fabric with colorful swirls, and wrapped it around her. Her shivering eased. Now she looked like the picture of a girl he’d seen in one of Jon’s foreign papers, all shawls.

“I’ll protect you,” Tam told Kara. “Whatever you think of us lot, we care about you. Last summer meant something. We were allies in the thicket then, and this is sure looking a thicket now.”

“A thicket?” Kara croaked. “Don’t speak idiot. Let’s get out.”

Tam tried the old door, and found it open. It led to a corridor. He wasn’t sure it was the right corridor, but he set off down it regardless, with Kara in his arms.

Anna and Varden walked down the hallway, past uninspired portraits of bearded men and solemn women, and sculptured busts that were obviously not from Narmos. Anna paused and frowned at one of the sculptures. “There’s something wrong with this.”

Varden stopped to look at it, too. “No, I think the nose and ears might actually be that proportion on purpose. You never met my uncle.” He spoke lightly, but there was nervousness beneath his voice.

“I meant the eyes, Varden. Look.” The eyes in question were welling with dark red drops. “The thing is weeping blood.”

“Porous stone and a chemical compound, or perhaps just liquid pumped through small channels,” Varden said. “It’s all rather pathetic and annoying, really.” But he pulled her away from it and led her on down the hallway, keeping himself between her and the line of busts, all of which now seemed to be weeping.

Anna looked up at a painting of a young girl in morning sunlight. The colors were poorly done, in dull, even blocks. She blinked, and suddenly the sun in the picture was setting, and the golden light had turned to red. Anna squeezed Varden’s hand and breathed a little blessing to herself, one her mother had taught her when she was very small. “The One hold and guide us, set our feet on true paths that we may find sure footing in the depths and on the heights. One keep us guarded, wherever we may roam.”

“What’s that? You’re not panicking, are you?”

“Prayer isn’t panic,” Anna said. “If this house is an anchor for spirits, they aren’t good ones.” Prayer seemed only practical to Anna, like having packed a candle in your pocket. She wished for a candle now, or even Varden’s short-lived matches, any bit of light to hold in the darkening corridor.

“There are clear scientific explanations for everything we’ve witnessed,” Varden argued. “I think it’s a bit early to invoke all the pantheon of Helianth.”

“Tam!”

“What pantheon is that from?” Varden asked.

But Anna only had eyes for the familiar figure that had appeared down the hallway, carrying an awkward bundle of bright-colored cloth. “Tam, the oddest things are happening in this house.”

Tam smiled at her, but the smile didn’t take away the worry around his eyes. “I’ll say so myself. I’ve had all sorts of bother with windows and doors, and look what I found in the parlor.” Kara peered out, doleful and almost unrecognizable, a dark-skinned foreign waif swathed in veiling fabric.

“Hullo, why did you come in?” Varden frowned at Tam.

“I heard a noise,” Tam said, “and found this.” He hefted Kara. “She shouldn’t ought to be here. She’s not well.”

Varden leaned over to look. “Collecting young foreign girls in his parlor doesn’t look very good for Pumphrey, no, but what exactly do you intend to do with her?”

“Well, get her out.” Tam exchanged a relieved look with Anna. Varden evidently didn’t recognize Kara as the foreign thief from his father’s accusations. She didn’t look like a dangerous criminal, after all, sick and wrapped in—those weren’t blankets, exactly. Curtains? “We get her some air, and get all of us out of this here knotty bit of twine.”

“Thicket,” Kara muttered, incomprehensibly.

“Right,” said Varden. “Which stairs did you take to get here?”

“Stairs?” asked Tam.

“This is ridiculous.” Varden crossed his arms and stared around at the ever-shifting house. “Look here, let’s take those.” He pointed through an open door to a stairwell leading down.

“Can we get out through the cellar?” Tam asked Anna, as they followed Varden.

“I don’t know where those go,” Anna said. “But I don’t like the look of the shadows back there.” She waved further down the hallway, where a group of shadows without people to create them were shifting about ominously.

“Right,” said Tam, setting a brisker pace toward the stairs.

They trotted down one flight of rather dingy steps of the sort that might lead to the servants’ wing. The door at the bottom, however, opened out onto a landing that overlooked a great, open expanse. Above them rose a curved dome of glass, through which the newly risen crescent moon shone in the night sky. Down from the landing ran twin sets of curved stairs, descending on either side to a parquet ballroom floor, big enough for a hundred dancers to whirl around. The people moving about down below weren’t dancers, though. The household staff, maids and butlers in their severe dark uniforms, were busy unpacking big stone shapes from crates full of straw. They worked in unison, pushing the heavy stone slabs across the ballroom floor using a series of rollers. Anna had often seen the workmen at dig sites move stones in just such a way. Never so quietly, though. No one shouted orders or even spoke at all, just lifted and pushed in perfect silence.

“How did they get all those huge stone slabs up, or er, down, all them steps?” Tam wondered aloud. His voice seemed loud in the silence, but none of the servants lifted their heads to look up at the landing.

Varden ran to the edge and stared down, with a sudden indrawn breath. “It can’t be! They were never found, never documented. The ziggurat crumbled ages ago, and none of the inscriptions were recorded in the mortuary temples, and, and . . .” His hands opened and closed on the railing as he stammered for words.

“What are they?” Anna asked.

“The lost panels from the temple of Narmos,” Varden breathed, in that same awestruck tone with which Djaren and Jon greeted inscriptions, burial chambers, and dead languages. “The ceremonial inscriptions of the high priests, the focus of their entire mythology and governmental structure. I searched through the whole ruined complex. I thought I’d searched . . . But this imposter, this, this thief, must have been there before us.”

“Are you sure they’re genuine?” The Blackfeathers had come across plenty of fake artifacts in their travels, Alarnan funerary inscriptions or painted Helian urns being offered at bargain prices to the unwary. Varden the skeptic was turning a bit too suddenly into a believer, and that bothered Anna every bit as much as the shifting doorways and the moving shadows.

Varden turned to her, eyes alight, though she wasn’t sure he even saw her through his archeological daze. “It’s exactly as I wrote about it in my thesis. See how they’re setting up the tablets? The circular shape with the two protruding crescents, that’s the pattern from the top of the ziggurat, conforming to the four arms of the temple. It’s echoed in the cliff inscriptions at the entrance of the valley. Menlington thought the shapes were bull’s horns, for strength, but I’m sure the astronomical significance is far more—”

“So they’re recreating the top of the ziggurat?” Djaren’s cheerful lecture on depredations came back vividly to her mind.

Tam must have been thinking the same thing, because he shifted uneasily, back toward the open door to the stairway. “The one with the smiting and bolts of lightning and evil possessions and all? That accounts for the house, I reckon.”

Ignoring Tam, Varden answered Anna. “They’re recreating it quite accurately, really. Compared to the rest of the rubbish around the place, this is, well, truly miraculous.” That was hardly the word Anna would have chosen. Varden turned back to look over the ballroom again, pointing from stone slab to stone slab. “There’s the blessing for opening the eyes, and the one for opening the ears. There’s the lost invocation to Kesh, full of the usual nonsense, though rather poetically put, I suppose.”

He began to read aloud, in what Anna could only assume was the language of Narmos. To Anna’s horror, the servants, who until now had failed to notice their presence up on the landing, all stopped moving and raised their faces toward Varden. Their eyes looked strange, fixed and empty.

“Stop it!” Tam, balancing Kara in one arm, grabbed at Varden with the other, pulling him back from the railing. “What d’you want to go reading it out loud for?”

Varden scowled and wrenched his arm away. “Don’t presume, peasant. What do you know about Narmos?”

The servants were still staring up at them. “Varden,” Anna whispered, “I don’t think we were meant to see this. And if we don’t get out of here and tell someone about it, no one’s ever going to know.”

Varden’s eyes went wide. “The Society, of course! They must be told of this crime against scholarship. I’ll compose a formal letter of complaint. No, I’ll stop by their offices first thing in the morning.”

Warning Lady Hellin and Eabrey was a little higher on Anna’s list than complaining to the Archeological Society, but if that was what it took to get Varden moving . . . She tried a hand on his arm, and he didn’t shake her off. “We’ll alert them, then. We’ll get these inscriptions into a museum, and published in the proper papers, and everything. Come on!”

She pulled him, still glancing backward in protest, down the dingy stairs that, thank the One, hadn’t vanished in the meantime. Tam sighed with relief and ran after her.

* * * * *

Ellea lay on her back and watched stars begin to appear in the darkening sky. “No comets yet,” she observed. “It’s quite a clear night, really.”

Jon, sitting nearby, smiled hesitantly.

Djaren perched in the paper and paste observatory he’d built at the top of the gazebo, staring upward through his spyglass. “I think I see a nebula. And those are three little stars clumped together, not one, in the beak of the Swan.”

“You’d better come down from there. I think you’re going to be in trouble,” Ellea said. “There are people coming down from the hotel.”

Jon sat up and peered over the gazebo rail. “That maid doesn’t look very pleased,” he said, then jumped, as sudden radiance flashed from his palm.

He stuffed his hand in his pocket while Ellea lit a lantern, both to mask Jon’s light and to see who was coming. Ellea could hear Djaren scuttling about above, trying to clear away his paperboard constructions, maybe. He skidded down suddenly, landing at the gazebo entrance in a little flurry of paper.

“I’m sorry if we’ve made a mess. We’ll tidy it all up,” he said in Germhacht to the people approaching. They did not answer. Ellea looked around Djaren’s back to see eight adults, all in simple, dark, fine clothing like the servants and staff at the hotel. One woman was clearly a maid, apron and all. Even though Ellea could not recall having seen any of them in the hotel before, they looked oddly familiar.

“Are you the night shift?” Djaren asked, looking at the grim advancing faces. “Because we are hotel guests, and I did ask permission to be here.”

Jon, close beside Ellea, whispered, “It’s getting brighter. Something’s wrong.”

The people were nearly upon them. Ellea felt Djaren tense. He stared from one face to the next. “Pumphrites!” he yelled. “Half of them are Pumphrites in plainclothes! Run!”

The woman in the lead, the maid, reached out with one oddly claw-like hand, grabbed Djaren by the front of his jacket, and threw him with horrific strength into the bushes three yards away. He fell with a cry, tangled partway through a topiary.

Ellea and Jon retreated. Jon pulled his hand from his pocket and bright light burst out from his palm, briefly blinding the oncoming Pumphrites, and giving Jon and Ellea a chance to scamper over the gazebo’s ledge and drop down into the garden.

Ellea grabbed Jon’s other hand and ran toward the hotel’s hedge maze. “What’s going on?” Jon asked, breathless from running. “What do they want? They don’t look quite themselves. They’re not talking.”

“That is certainly out of character,” Ellea allowed, pulling Jon around a short series of bends in the maze.

“Should we be leaving Djaren alone out there, with them?” Jon asked.

Ellea paused, torn. He’d flown like a rag doll and made a noise on falling. He was bigger than her, and always trying to be the heroic one, playing at being Father with none of his powers.

“Probably not,” she said, “but he is rather clever, you know.” Her brother’s voice rose in a challenge somewhere behind them. She frowned. “Not as clever as he thinks he is, though.”

“My hand did something, did you see? Maybe it will again,” Jon said. “It doesn’t feel right, running.”

“I think they are after us, not Djaren,” Ellea pointed out.

“Oh. Why?”

“I don’t know. Maybe it’s to do with your hand.”

Jon blinked. “Oh, dear. Maybe if I ran off alone–”

“Don’t be silly or tiresome. We’re in this together.” Ellea pulled Jon toward her, and down a left turning, remembering how the maze went, from having seen it out the windows.

They heard Djaren’s voice again, a cry of pain, and a shout suddenly muffled.

“He’s in trouble,” Jon said.

“How annoying of him. We’ll have to rescue him, of course, but I think it would be smartest to alert the concierge and the real hotel staff. If we double back down this way, we can squeeze through a bare patch and run in near the kitchen entrance.”

“That’s clever,” Jon said.

“Of course it is.”

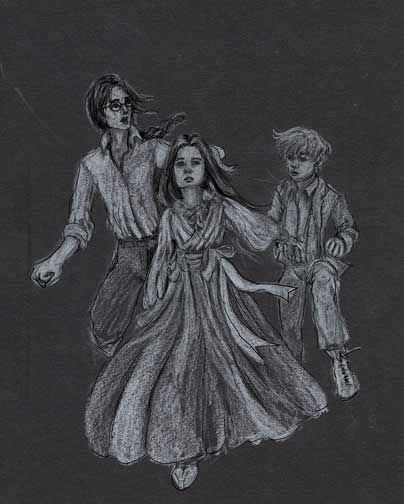

The plan nearly came off. Ellea peered out, looking both ways, then yanked Jon after her in a sprint toward the kitchen doors. But then the maid was suddenly in front of the doors, waiting for them, and a man came round another corner with Djaren, holding his arms twisted high and hard behind him. He’d been gagged. Djaren used the distraction of their appearance to kick hard at the man’s shins. He broke free, spit out the gag, and dashed toward them. “Back in the maze, and scream bloody murder!” he said. “Don’t get close to any of them, they’re stronger than they should be.”

Ellea led the way back into the maze, and Jon after her. She glanced back over her shoulder to make sure Djaren was following. It was good they were all together again, though she didn’t know where they should run next. Her plan hadn’t worked, and she was too breathless and harried to consider any alternatives, except getting away as quickly as possible. She hated it when people didn’t give her time to think. She wished she were allowed to ignore the bounds of mental privacy just this once, and stop their pursuers herself.

They all made it together deeper into the maze. Ellea thought she’d been bringing them through the right turnings, but it wasn’t fast enough, and that man and the maid were close on their heels. Ahead, Ellea heard people moving and realized that the Pumphrites were trying to corner them. Djaren was shouting in five different languages, everything from “Kidnapping!” to “Fire!” to other more unlikely and inventive warnings. Jon added shrill affirmatives to the ones he understood.

“Aren’t we just giving away our position?” Ellea panted.

“Do you suggest that we could escape this by stealth? Because I am open to options,” Djaren gasped back.

“You’re the one with ideas,” Ellea said, a little harshly.

“I can neither fly nor dig like a mole, so I fail to see a method of escape from superior numbers,” Djaren said. “If they have both entrances to the maze blocked, which I imagine they have by now, our only option for surprise is going through a wall somewhere. Maybe Father or even Tam could thrash them, but I certainly proved I can’t, unarmed.” Djaren sounded unhappy. No bruises showed yet on his skin, but he was cradling one arm with the other.

“I see a place ahead where we can maybe squeeze through.” Ellea pointed.

“Good. You and Jon go first, as I’m bigger and will likely be slowest. If you see a chance, run out where there are people and get help.”

“Don’t do anything heroically stupid,” she told him.

“I’ll try not to.” Djaren made a face. “Now go. Go!”

“I’ll try not to.” Djaren made a face. “Now go. Go!”

Ellea squirmed out through a thin patch, scratched and annoyed, and helped pull Jon after her. Djaren scrambled out through the hole they’d made with little problem, and they dashed off through flower beds to the easternmost gate of the hotel grounds.

Ellea cast a glance back as they ran, and saw something dark swarm up over the hedge wall and drop to the ground on the other side. It landed on all fours, like a crouching spider. Ellea blinked, and watched another shape do the same thing. She wondered, even if she broke the rules and touched their minds, if she would find anything human there to stop. Suddenly she felt much more frightened. The light from Jon’s hand was glowing brilliantly all around them. Surely someone would see that, wouldn’t they? And come to help?

Djaren grabbed her up around the waist and ran with her, so they could all move faster. He lifted her up onto the closed gate and helped her climb by pushing her feet up higher so she could reach the denser ironwork at the top. Jon found a way up, bracing himself against both the stones on the wall and the gate lattice. They both made it safely down to the other side together.

Then Djaren began to climb. He was only just at the top when their pursuers caught up, all moving oddly, quick and jerky, with eyes strangely wide and bright. One man grabbed at Djaren’s leg.

Jon turned and ran back to the gate.

“What are you doing?” Ellea paused to shriek after him. She didn’t want to lose them both and be left all alone.

“I don’t know,” Jon called. “But oughtn’t I be able to do something?”

Djaren had both arms wrapped tight around the iron work on top of the gate. The Pumphrites clawed at him with their grasping hands. He kicked at them and lost a shoe.

Jon grabbed the gate with his madly glowing left hand, and the black iron bars were limned with lines of silver. The Pumphrites shrieked and recoiled. One man who’d actually touched Jon’s hand fell back with smoking fingers.

Djaren kicked free and scrambled up over the gate. He dropped down on the other side a little too hard, with a choked curse. “Run!” he shouted, and pulled Jon after him, shoving him to run ahead while he limped after.

Jon seemed reluctant to get too far ahead of Djaren. “Are those people possessed?” he asked Ellea.

“Yes, probably,” she said, looking back to see them swarming the gate like monkeys.

“Run,” Djaren insisted, catching up.

“My hand did something.”

“It did, yes, thank you very much,” Djaren said.

“Here’s a carriage coming,” Ellea said. She dashed out before it and yelled “Stop!” At the same time she gathered her will and repeated the command with the full force of her mind. Forget the rules. This was the one thing she could do to save them. The carriage reined up suddenly before her, horses rearing and snorting.

The door of the carriage opened, and a woman’s voice called out in Germhacht from the darkness inside. “Why have we–? Oh, dear, whatever is the matter?”

The children hurried to the carriage. Jon pointed back to the dark shapes dropping down from the gate. “Those bad people are chasing us! We need to get away from them, please.”

“Oh, my,” the woman said. “Why, they don’t look at all right. Do get inside, dears.”

Djaren helped Ellea up, and then Jon, who paused with one foot in the carriage as his hand blazed suddenly bright, lighting the face of the woman inside, with her purple crystal earrings and brightly colored turban. Her eyes were too bright, and her smile too wide. “One ought to be enough,” she said.

Someone grabbed Ellea from behind and shoved an awful smelling cloth against her face. She watched, helpless and furious, while the carriage driver raised his whip and hit Djaren. Another man kicked Jon in the chest, and he fell back, letting go of the carriage, and landing on top of Djaren. Ellea’s will slipped away like spilled tea even as she tried to direct it into an outraged command. The carriage pulled away, taking with it her last fading view of the boys sprawled on the cobblestones.